As a human being, you are inevitably fallible, biased, ignorant, and self-serving. It is highly likely that most of what you think and say is at best partial and misleading. Much is outright mistaken. Does this mean that you shouldn’t contribute to public debate? Some thoughts:

In recent weeks, I have published a few pieces that attempt to make contributions to “public debate” (e.g., here). Of course, this is an extremely grandiose way of putting it. Hardly anyone reads anything I write, and my publications almost certainly have no real-world consequences.

Nevertheless, in making such contributions I always feel anxious. I think of the inevitable flaws in what I write, the weaknesses in my arguments, and my ignorance concerning the vast literature relevant to what I write about. I also look back on times – sometimes in the embarrassingly recent past – when I was wrong, unreasonable, biased, arrogant, or uninformed (in some unfortunate cases, all at once). By simple induction, I’m led to believe that there is a good chance such things apply to whatever I think now as well, even if I’m less capable of detecting it in the present.

In saying this, I don’t want to present myself as highly altruistic. What’s probably happening “under the hood”, I suspect, is that I’m worried other people – people more knowledgeable, intelligent, and fair-minded than me – will judge me harshly for my flawed contributions. After all, I judge my past self harshly for flawed contributions now I have (what I take to be) a clearer vision of things.

This raises a difficult question: What are the appropriate ethics – more precisely, the appropriate social norms – that should govern contributions to public debate? And what norms should we apply to those who judge public debate?

I’m sure many people have written about this. I’ve not read much of this work, however, so here are some largely – and ironically – uninformed reflections.

The Epistemic Commons

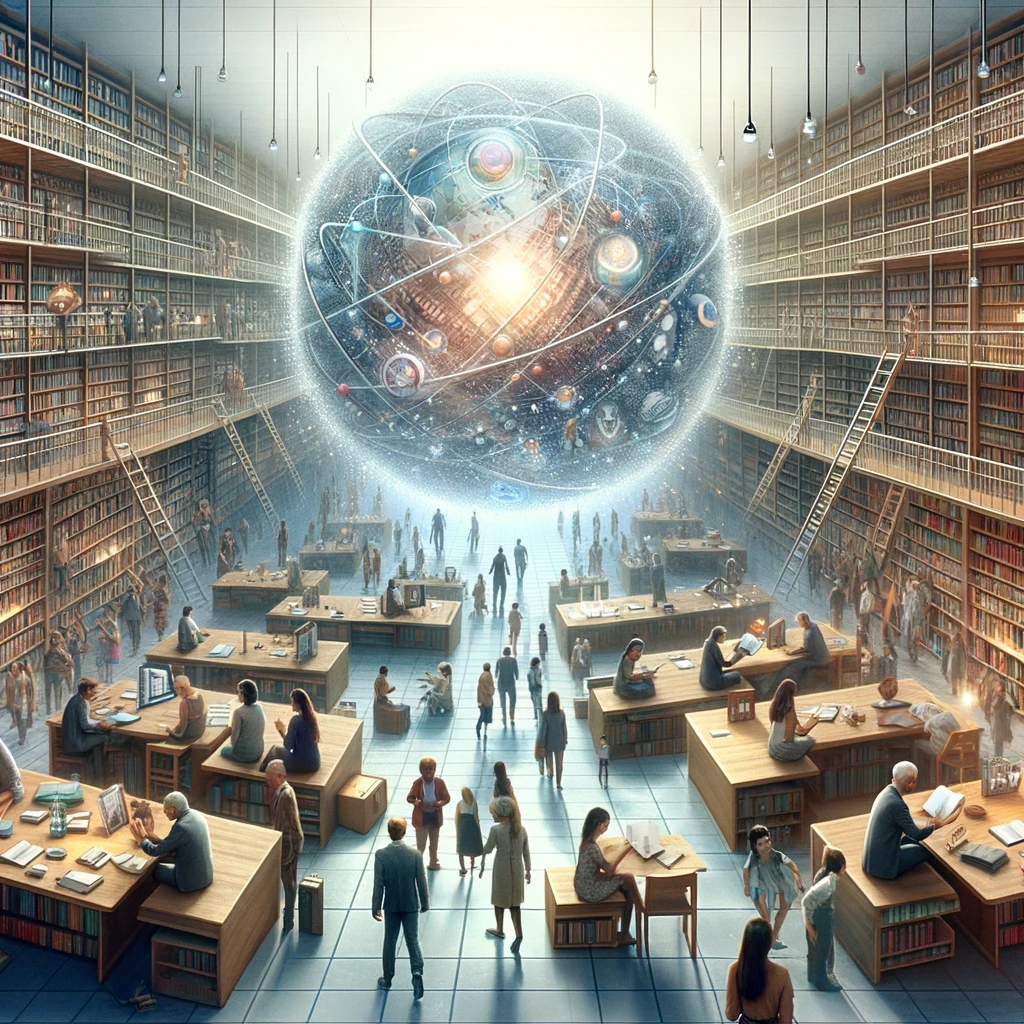

Humans are an epistemically cooperative species. We rely on a division of cognitive labour. We acquire most of our beliefs about the world outside of our immediate experience from others. We are beneficiaries – and frequently victims – of what Joshi calls the “epistemic commons”, the “stock of evidence, ideas, and perspectives that are alive for a given community.”

As with all cases of cooperation, the cooperation required to produce and maintain the epistemic commons is vulnerable to certain recurrent threats.

Most obviously, people can poison the epistemic commons to advance their interests. Liars, propagandists, and disinformation campaigns deliberately pump out self-serving falsehoods and misleading content. This is a flagrant transgression, and will be punished as such, both directly but also reputationally, in all but the most dysfunctional societies. So, this is the first rule of public debate: don’t intentionally poison the epistemic commons.

Less obviously but just as importantly, there are epistemic polluters. They don’t intend to poison the epistemic commons; instead, they poison the commons as a byproduct of contributions aimed at other goals. In attempting to promote their interests – seeming smart, winning support from ingroup members, getting attention, and so on – they add ideas to the epistemic commons that are low-quality, false, or misleading. These epistemic flaws with their contributions are negative externalities; they are a cost that epistemic polluters do not care about because they do not affect themselves, only others. Your average attention-seeking social media bullshitter is a good example of an epistemic polluter in this sense. So, we have a second rule: don’t be an epistemic polluter.

Then there are epistemic free riders. These reap the benefits of other people’s contributions to the epistemic commons without offering any contributions of their own. This is a kind of transgression, especially if people have the knowledge, abilities, and time to contribute. However, as a norm violation it is complicated by the following fact: audiences who attend to and acquire information from others do not typically benefit from their cognitive labour without giving anything in return. They give something in return: their attention – and sometimes their gratitude, appreciation, interest, deference, and respect.

Humans achieve cooperation in part through prestige economies. To incentivise individuals to sacrifice for others, we pay them in an invisible social currency that ambitious people often place a high value on: status. The result is everything from competitive altruism, whereby individuals compete for prestige through altruistic acts of extraordinary self-sacrifice, to the credit economy that powers modern science, within which scientists devote considerable time, energy, and ingenuity so that they can win credit – esteem, recognition – for making novel discoveries.

This also helps to explain why people often invest so much time and energy in participating in public debate. It’s not just that they like the sound of their own voice or the look of their own tweets: people want to be liked, respected, deferred to, and admired, and audiences confer these social benefits on those they perceive to make useful or interesting contributions to a public conversation. This is the flip-side of punishing epistemic poisoners and polluters: we reward those that we perceive to make good contributions to public debate.

The Ethics of Public Debate

From these considerations, it seems we can extract the following norm: One should contribute to the epistemic commons only if one has good reason to believe one’s contributions will have positive epistemic value (e.g., are true, reasonable, well-supported by evidence, etc.). Because people’s behaviour is typically sensitive to social incentives, this also suggests a norm for judging contributions to public debate: reward those contributions that you judge to have positive epistemic value (as contrasted with those that you merely find congenial, entertaining, inspiring, and so on); and punish those that don’t.

I think this is potentially too strong, however. There are good reasons to believe that as individuals we should strongly expect our contributions to public debate to be deeply epistemically flawed. As I stated at the outset, I think most of what we think as individuals is partial, biased, distorted, and very often wrong. In fact, one of the reasons we need the epistemic commons in the first place is because as individuals we are hopelessly biased and ignorant.

Given this, I’m inclined to think a better norm is this: One should contribute to the epistemic commons only if one has good reason to believe one’s contributions will improve the quality of the commons. Of course, there is considerable scope for self-deception in such assessments. Nevertheless, what ultimately matters to public discourse and social behaviour more generally is social norms and incentives. Given this, this norm implies a standard that audiences should bring to bear in judging others as well: reward those contributions that improve the epistemic commons; punish those that don’t. If one judges people harshly for being biased, wrong, uninformed, and so on – flaws which seem inevitable – this will likely discourage people from improving the stock of common ideas and wisdom, and end up selecting for participants in public debate who exhibit pathological levels of overconfidence.

In sum: We shouldn’t demand that people inject truth into the epistemic commons. In many cases, that’s too much to ask. We should ask instead that they make a good-faith effort to leave it better than they found it.